Kidney Stones

Kidney stones are a fairly common problem and can cause some of the worst pain that a patient can experience. A kidney stone begins as a tiny crystal and gradually grows in size. When a stone begins to travel through the urinary tract, it may cause symptoms and problems.

Sometimes stones are flushed from the body with little or no sensation. But when a stone is large or jagged, it may become lodged in the ureter (the tube that connects the kidney with the bladder), in the bladder, or in the urethra (the passage that leads from the bladder to outside the body), and it can then cause intense pain.

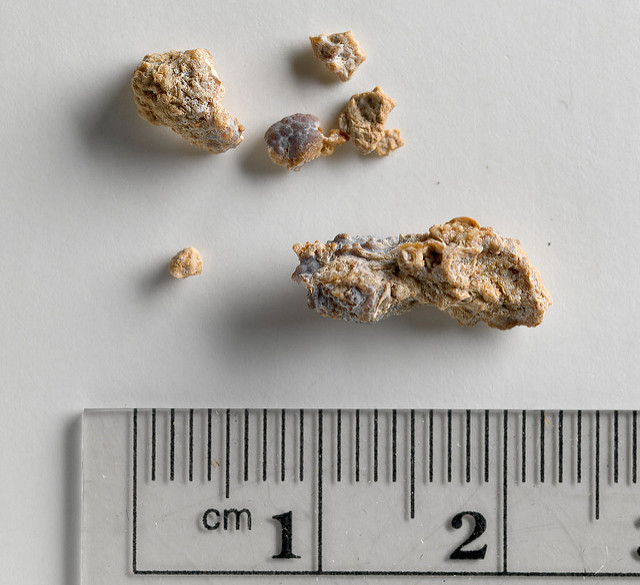

Stones can be as small as a grain of sand, as large as a pearl, and sometimes even larger. They can be composed of a number of materials. Here are four examples:

- Calcium oxalate – this is the most common type of stone. It is formed from a combination of two substances that are normally contained in the diet: calcium and oxalate.

- Uric acid – this type of stone is formed as a result of having too much uric acid (a breakdown product of protein) in the urine.

- Struvite – these stones form in the presence of chronic urinary tract infections. They contain several different minerals and can grow to enormous size, even filling the urinary system in a branched form called “staghorn” calculi (stones).

- Cystine – this stone is rare and forms only in people with a specific hereditary disorder.

Risk Factors for Forming Kidney Stones

- Heredity – About 25% of people who form stones have a close relative (such as a parent or sibling) who has also had kidney stones.

- Insufficient fluid intake – This causes the urine to be more concentrated, so that stone-forming components such as calcium are more likely to “precipitate,” or to form the tiny crystals that are the beginnings of a stone.

- Dietary factors – Intake of certain foods results in too much of certain stone-forming components in the urine. In such people, for instance, eating too much oxalate may increase the risk of oxalate stones, or eating too much protein may contribute to the formation of uric acid stones. Calcium or vitamin D supplements, when taken in large amounts, may also increase the risk of stone formation.

- Bowel disease – Intestinal disease such as Crohn’s disease or “short bowel syndrome” due to gastric bypass surgery may increase the risk of forming calcium oxalate stones.

Symptoms and Signs of Kidney Stones

Pain – The most obvious symptom of kidney or bladder stones is intense pain in the flank area, which is in the back, just at the lower edge of the ribs on either side of the spine. The pain begins abruptly, at the moment that a stone becomes lodged in the ureter. Urine flow is then blocked, which causes urine to back up into the kidney. The kidney then swells and enlarges, stretching the pain-sensitive capsule, or thin covering around it.

Kidney stone pain is referred to as “colic,” meaning that it comes and goes in waves as opposed to being a steady continuous pain. Pain from kidney stones is described as being as severe as that of childbirth. Patients with renal colic usually find it very difficult to hold still, and are in constant motion, pacing and writhing. Often the pain is so severe that it causes nausea and vomiting.

Although the pain starts in the right or left flank area, it may move as the stone travels down the ureter on its way from the kidney to the bladder. The pain may travel from the back, around the side of the trunk to the lower part of the abdomen in the front, and even down to the groin.

Blood in the urine – Passage of a kidney stone may also cause blood in the urine.

Urinary tract infection – In some cases, an infection of the kidney may develop behind a kidney stone, causing fever, chills, and cloudy urine.

Kidney failure – Blockage of the ureter by a stone may also prevent the kidney from doing its normal job of excreting salt, water, and waste products, and may cause temporary or even permanent kidney failure if left untreated.

Diagnosis of Kidney Stones

The diagnosis of kidney stones is usually strongly suspected because of the patient’s history, with the abrupt onset of severe flank pain with or without blood in the urine. The following studies are used to diagnose kidney stones:

- X-ray – The diagnosis can sometimes be confirmed by a plain x-ray of the abdomen. A stone shows up as a white object if it contains calcium (which about 80% of stones do).

- Ultrasound – A kidney ultrasound can show the presence of a stone: sound waves cannot pass through a stone, so the stone “casts a shadow” on the ultrasound picture.

- CT scan – A special type of CT (computed tomography) scan can also be very accurate at detecting small stones.

- Kidney Stone Analysis – Patients with kidney stones are often asked to strain their urine in order to recover the stone when it passes, so that the stone can be sent for analysis. If a stone analysis and/or a 24-hr urine collection is performed, your physician should be able to tell you what your stones are made of, and whether your urine contains too much or too little of the various stone ingredients.

On imaging studies, one important finding that radiologists look for is hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis (literally, “water in the kidney”) develops when a portion of the kidney becomes swollen because urine flow from the kidney to the bladder is blocked. As noted above, such a blockage can lead to kidney failure, which may even be permanent if the kidney stone is not passed or removed.

Treatment Options

Kidney stones often pass without any kind of medical assistance, but when they become lodged in the ureter, they cause pain and may disrupt normal kidney function. Common treatments for kidney stones include:

Increase Fluid Intake – The most common treatment prescribed for a kidney stone sufferer is large amounts of water and other fluids (but not iced tea, which contains oxalate, a common component of stones!). Because a person with a kidney stone is often nauseated due to the severe pain, it is sometimes necessary to give the fluids by IV rather than by mouth. In either case, the fluids result in an increase in urine flow, and the rush of urine through the ureter often expands the ureter and pushes the stone through into the bladder.

Pain medications – Pain meds (even narcotics such as morphine) are often given to relieve pain while the patient is waiting to pass the stone. In addition, there are other medications that may be given to relax the ureter, relieving spasm of the muscles of the ureter and allowing the stone to pass more easily.

If simple treatments do not work, it may be necessary for one of the following procedures to be used to either surgically remove the stone or to break it up into small fragments that can be passed in the urine.

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) – Shock waves generated in water (like very tiny tidal waves) can be very precisely directed into the abdomen to break up the stone into smaller particles that can be easily passed in the urine. Depending on the form of shock wave machine used, the patient either sits in a tub of water or lies flat on a table. Because this procedure is painful (with up to hundreds of shock waves being focused on the kidney in a single session) it is performed under general anesthesia. Following the procedure, there is often pain as the patient passes the many tiny stone fragments into which the large stone has been shattered.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy – Also known as tunnel surgery, this method makes use of a tunnel-like surgical device that is inserted into a small hole in the patient’s back and positioned on the kidney. An instrument is manipulated through the tunnel, allowing the surgeon to find the stone and remove it.

Ureteroscopy – When the stone is located in the ureter, a device called a ureteroscope, which looks like a flexible wire, is inserted into the patient’s urethra and threaded through the bladder and up the ureter to where the stone is lodged. The scope has a camera attached to it, so that the physician can see the stone. The kidney stone is either caught in a basket-like device and extracted from the ureter, or broken up by ultrasound waves into tiny fragments that can then travel down to the bladder and be passed.

Prevention

In order to reduce the chance of recurrence of kidney stones, the following may be useful:

High fluid intake – Kidney stones form when the concentration of certain substances (such as calcium) in the urine reaches a critical level. Therefore, it is wise to keep urine dilute, in order to keep the concentrations of stone components as low as possible. A rough guideline is for a patient to drink approximately 8 glasses (2 quarts) a day of water and other fluids, aiming for a urine output of approximately 2 quarts per day.

Dietary modification – A 24-hour urine collection may reveal that the urine contains too much or too little of certain substances that make kidney stone formation more likely. If abnormalities are detected, the diet can be changed to reduce the likelihood of stone formation. Listed below are some dietary modifications for stone prevention:

Oxalate (high) – If your urine contains too much oxalate, your dietary oxalate intake can be reduced. Foods high in oxalate include: rhubarb, nuts, chocolate, and tea.

Calcium (high) – If your urine contains too much calcium, the amount may be reduced by a medication called a thiazide diuretic. However, a high amount of urinary calcium may also be a sign of one of several underlying conditions (such as renal tubular acidosis or hyperparathyroidism), which will require further evaluation and treatment.

Uric acid (high) – If your urine contains too much uric acid, your protein intake can be decreased and/or a medication called allopurinol can be given to reduce the production of uric acid.

Citrate (low) – If your urine contains too little citrate, which actually inhibits stones from forming, citrate may be given in tablet form to help prevent stone formation.

Sodium (high) – If your urine contains too much sodium, which tends to promote more calcium in the urine, dietary sodium restriction may be advised to reduce the likelihood of forming calcium-containing stones.

Before undertaking any of these interventions, discuss with your doctor.

Learn more about the kidneys:

- Basic Information About the Kidneys

- Kidney Pain

- Signs and Symptoms of Kidney Disease

- Tests Used to Diagnose Kidney Disease

- Treatment & Management of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Kidney failure information:

- Kidney Failure – Understanding End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

- Hemodialysis

- Peritoneal Dialysis

- Kidney Transplantation

- Organ Donation and Transplantation

Articles about urinary disorders:

Hope Through Research – You Can Be Part of the Answer!

Many research studies are underway to help us learn about kidney stones. Would you like to find out more about being part of this exciting research? Please visit the following links:

For more information:

Go to the Kidney Diseases health topic.